Over the past two years, the Federal Reserve has largely reigned in inflation. The Consumer Price Index (CPI) has moderated from 9.1% to 2.4%, putting the Fed’s 2% inflation target within reach.

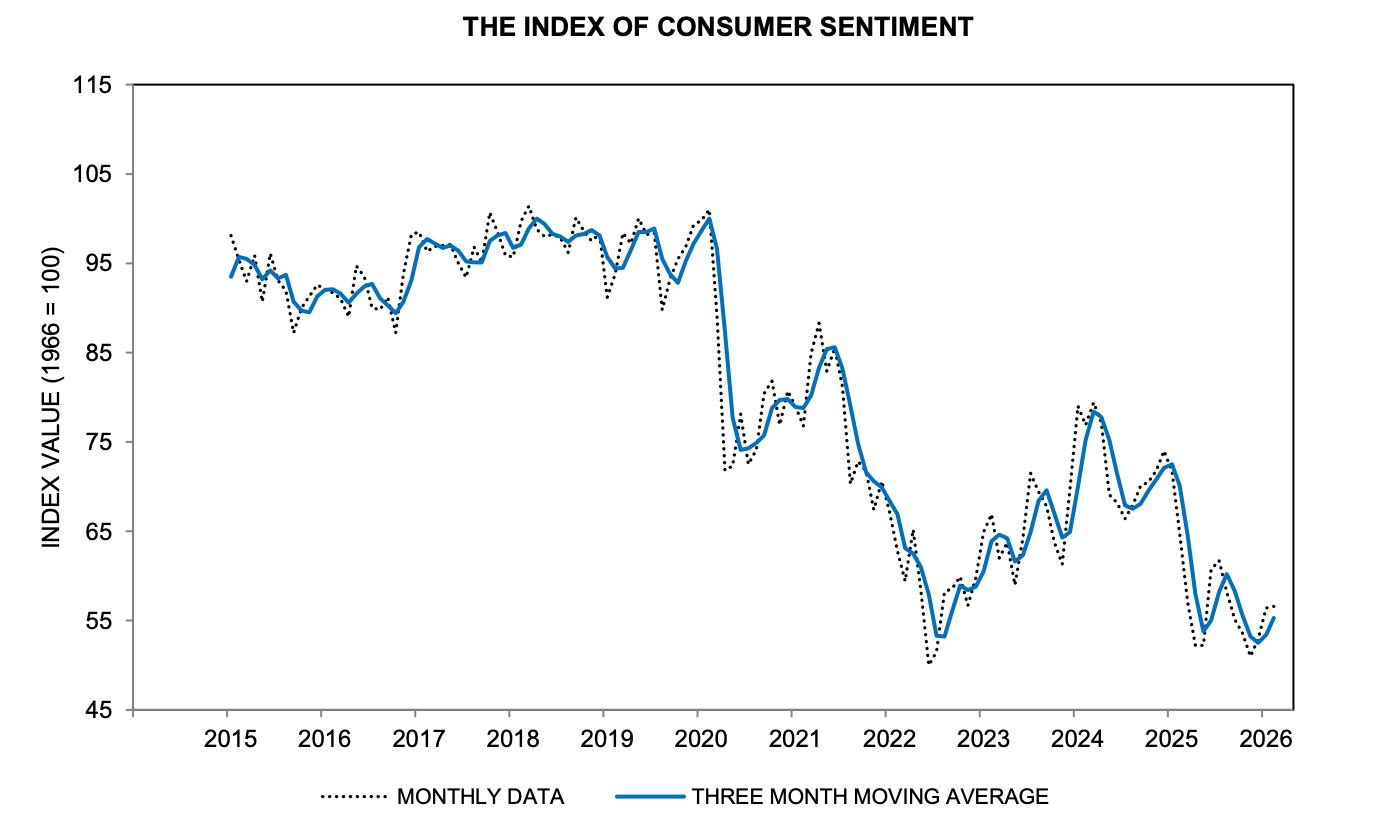

While it sounds like a victory, headline CPI numbers don’t tell the full story for the average American. Consumer sentiment remains near historical lows, and the University of Michigan reports that, for seven months in a row, over 40% of consumers have cited high prices as the primary reason for their financial distress.

To understand the lived experience of consumers and how inflation is actually impacting the economy, we have to dig deeper into the components of government-collected data sets like CPI and PCE.

Headline CPI and other inflation readings

The Consumer Price Index measures the average change over time in the prices consumers pay for goods and services. But here is where most investors go wrong: the headline number everyone discusses is only part of the story.

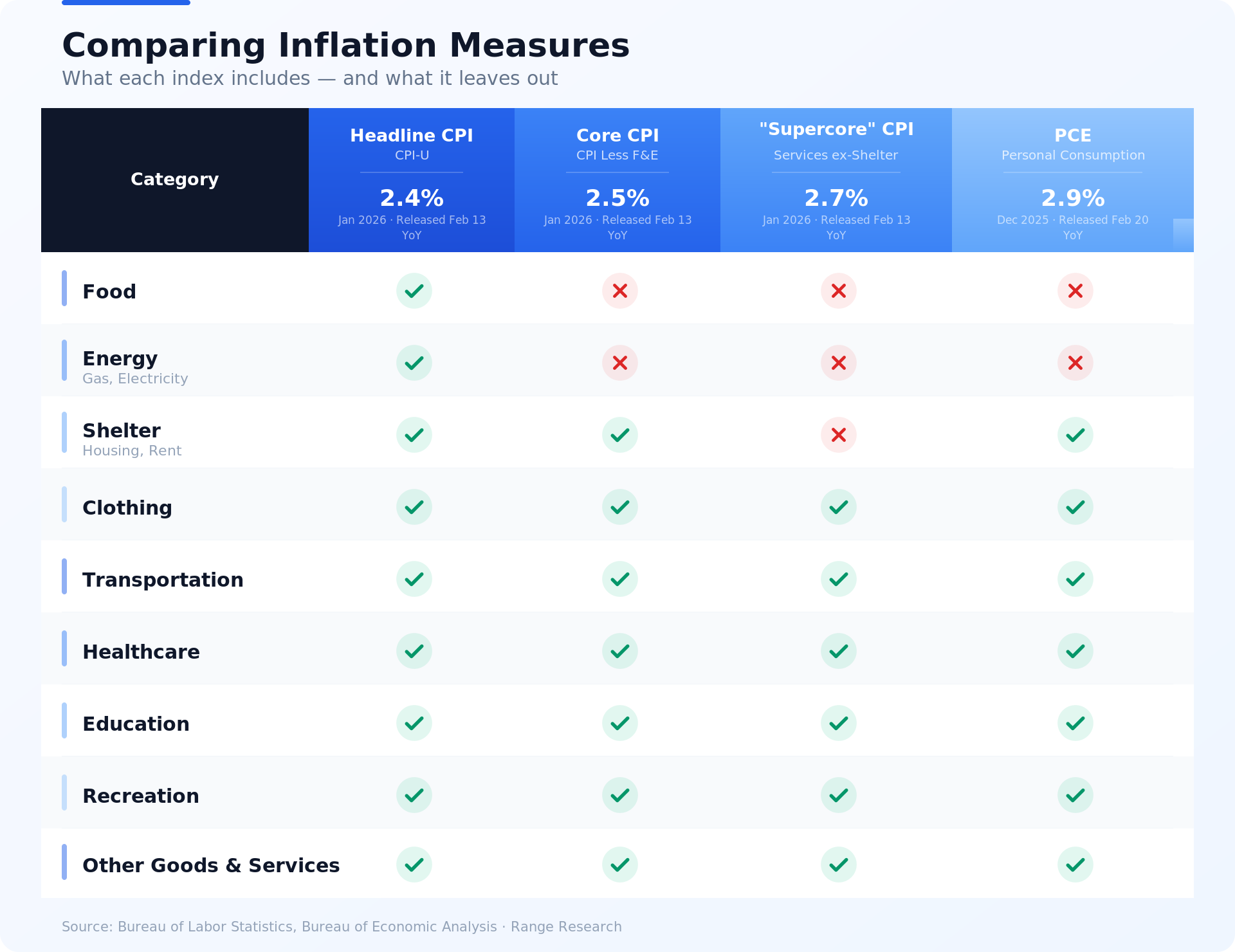

The CPI is constructed using a basket of approximately 300 goods and services, weighted by their importance in the average household's budget. Meanwhile, Core CPI, which excludes volatile food and energy prices, can often tell a different story.

Beyond these two, there are several other readings worth understanding. The "supercore" measure (services excluding shelter and energy) has become one of the Fed's most closely watched signals because it captures the stickiest, most labor-driven price pressures in the economy. There’s also the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) index. While technically a separate measure, it serves as the Fed's official inflation target and tends to run slightly below CPI.

Each measure tells a different part of the story: headline CPI captures what consumers feel at the register, core CPI filters out volatile food and energy, supercore isolates structural service-sector pressures, and PCE anchors Fed policy.

What these measures have been telling us

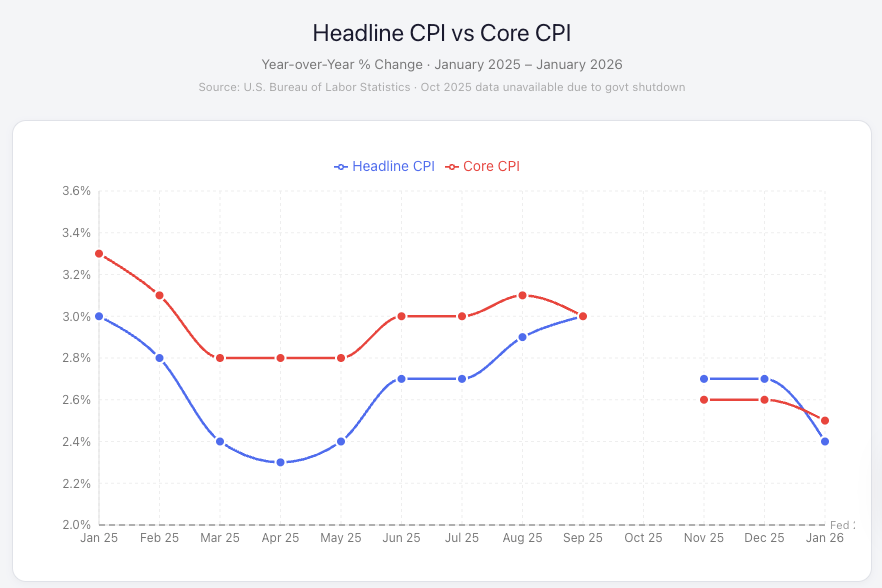

January's CPI report showed headline inflation below expectations at 2.4% - the smallest monthly gain since July. Bond yields dropped on the news, and expectations for the next rate cut were pushed out until mid-year. It was a sign from markets of growing confidence that the Fed's tightening cycle has done its job.

Despite the progress, core inflation has remained sticky. Only in the past few months have the two measures converged, but the damage has already been done. Sustained, elevated core inflation has worn into consumer finances and reflects a fundamental mismatch between how the media reports inflation and what actual households experience.

The K-Shaped Economy

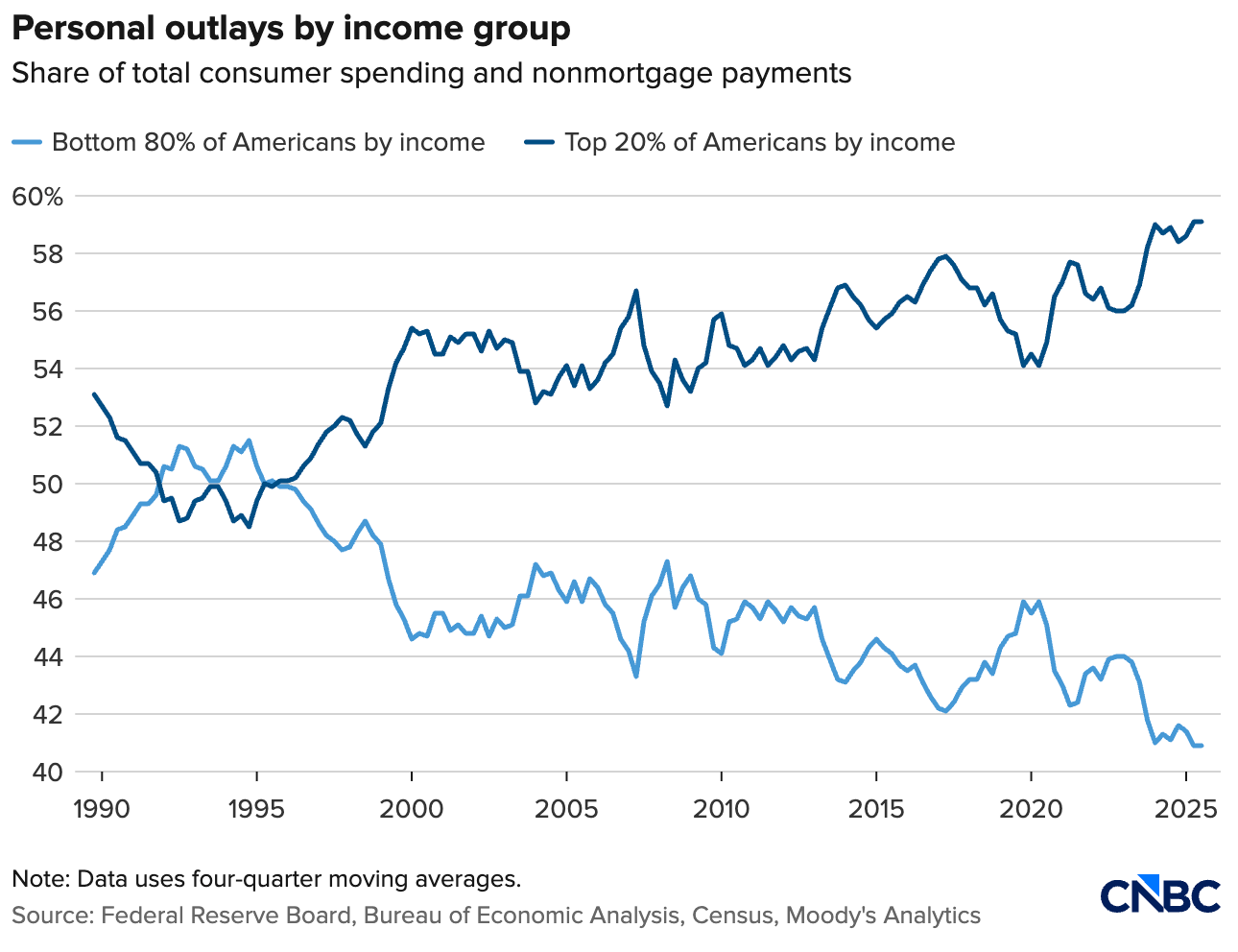

Part of the disconnect is that the battles of the past few years are leading to drastically different experiences across income brackets. This “K-Shaped” economy has seen higher-end consumers benefit from wage growth and strong investment markets, all while the average consumer continues to struggle.

Bloomberg recently estimated that consumers today spend $126 to buy what cost them $100 before the pandemic. Grocery and restaurant prices have risen by more than 30% since January 2020. Housing has been hit on two fronts: home prices are up 44%, and higher interest rates have nearly doubled the average monthly mortgage payment since early 2020.

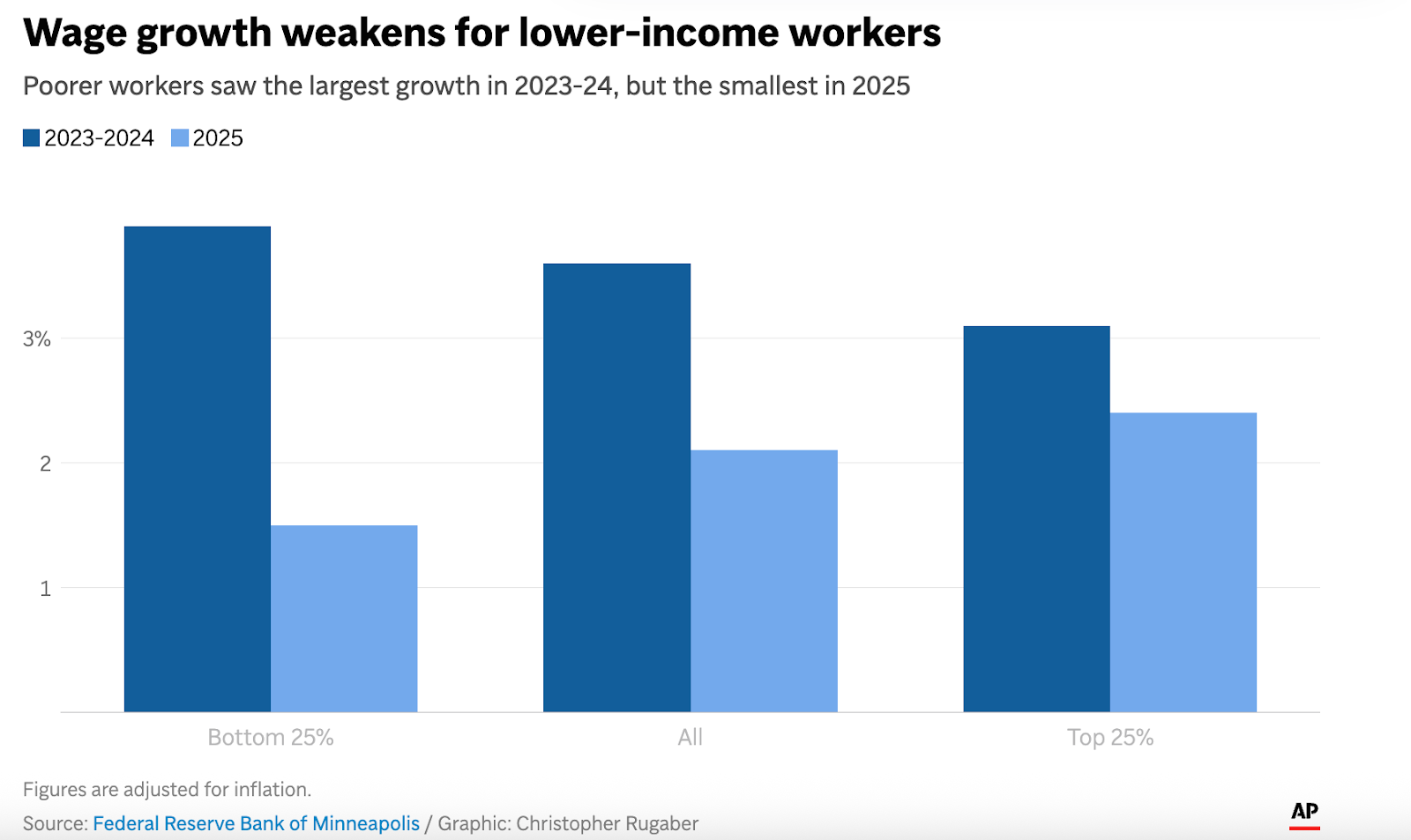

Lower-income households saw the fastest wage growth after the pandemic, but that advantage has largely eroded over the past year or so. This has led to a drawdown in savings to the lowest levels in over three years, as consumers tap into reserves to maintain their lifestyle. This has only just started to reflect in weaker retail sales data, while consumer debt delinquency rates are climbing to their highest level in nearly a decade.

The Range Take

The current rate-cutting cycle is predicated on continued moderation in core inflation, which has largely been cooler than expected for several months now. However, policymakers remain divided — some Fed members are concerned that inflation remains persistently above target and have feared an upward inflection from further tariff pressures. The appointment of a new Fed chair, with a hawkish history but a dovish mandate, further complicates the picture.

We believe that while headline inflation has moderated meaningfully, the K-shaped nature of this economy means the Fed can’t stand still. Lower-income consumers — who spend a disproportionate share of their budgets on food, housing, and energy — are still under significant financial strain, and the data is starting to show it: savings rates at multi-year lows, rising delinquencies, and softening retail sales.

This is the segment of the economy most sensitive to interest rate policy, and in our view, it’s where the Fed will increasingly need to focus its attention. That dynamic, in our view, creates a structural bias toward easing.

The Fed’s job could also get easier as the year progresses. We’re approaching the anniversary of last year’s tariff implementation, which means the base effects in inflation data could turn favorable in the coming months. And while still early, we believe the long-term disinflationary effects of AI-driven productivity gains are real and likely to begin showing up in the data — particularly in the service-sector costs that have kept core inflation sticky.

Taken together, we think this puts the Fed in a position to be more inclined to cut rates, even with a less-than-optimal inflation backdrop.

Disclosure:

This communication is for informational purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation to buy, hold, or sell any security. Forward-looking statements involve risks and uncertainties. Past performance is not indicative of future results.

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)